Chapters 10.5

10.5 - Sheep and Goat Pox Vaccines

Mark Shorter, University of Guelph, Canada

Suggested citation for this chapter.

Shorter,M. (2022) Sheep and Goat Pox Vaccines, The Encyclopedia for Small Scale Farmers. Editor, M.N. Raizada, University of Guelph, Canada. http://www.farmpedia.org

Background on Sheep and Goat Pox disease

Sheep Poxvirus (SPV) and Goat Poxvirus (GPV) are diseases that affect small ruminate animals such as sheep and goats (Rao and Bandyopadhyay, 2000, p 127). These diseases are from the genus Capri poxvirus and belong to the family of Poxviridae (Rao and Bandyopadhyay, 2000, p 127). Both are DNA viruses and have at least 147 genes (Rao and Bandyopadhyay, 2000, p 127). These diseases in small ruminates cause several detrimental health affects including pyrexia (fever), lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes), and skin/internal lesions (Rao and Bandyopadhyay, 2000, p 127). These diseases spread easily in crowded livestock populations, and transmission occurs through contact with the affected skin, inhalation, and through common carrier species like flies and mosquitoes (Rao and Bandyopadhyay, 2000, p 127).

Who does this disease affect

Although these diseases are considered ancient in many areas of the world, they are still actively being transmitted and detrimentally affecting several areas across the globe. To this day, both poxviruses for sheep and goats are considered endemics in several regions including India, the Middle East, in Northern and Central Africa (Rao and Bandyopadhyay, 2000, p 127). Both diseases do not affect all small ruminants equally, as health and age (infant ruminants are considered more at risk than adults) affects the likelihood of more severe disease (Rao and Bandyopadhyay, 2000, p 127). The virulence and strain of Sheep and Goat Pox have been found to also vary drastically between different livestock populations (Rao and Bandyopadhyay, 2000, p 127). Due to the mitigating factors above, there is no all-encompassing fatality rate accepted by researchers of these diseases, however the death rate has been found in studies to vary from 10%-85% (Aregahagn and Tadesse, 2021, p 1). The lower end mortality rate is still very consequential to the economic situation of struggling farmers, and on the high end can destroy a farmer’s vital livestock herd.

Impact these diseases have on small holder farmers in Africa

The detrimental impact of these diseases on small holder farmers in Africa cannot be understated. In many wealthy nations, small ruminant livestock are often overlooked as they do not play a significant role in their economies or population’s food infrastructure. However, in Africa, these livestock have several beneficial attributes that make them vital for small holder farmers. They are crucial as small ruminants “require a smaller investment, have faster growth rates, shorter production cycles, and greater environmental adaptability” (Yune and Abdela, 2017, p 1). These animals also play crucial roles in feeding smallholder farmers and their families as they provide an excellent source of protein and provide important extra income for these farmers to sell their extra meat to local populations (Yune and Abdela, 2017, p 1). These diseases have devastating economic effects due to both their high mortality rates and the damage these diseases cause to the health of animals (Yune and Abdela, 2017, p 1). Especially in sheep, the poxvirus can cause long-lasting damage to their wool, which is a precious economic item that these animals provide for these smallholder farmers (Yune and Abdela, 2017, p 1). A case study in Ethiopia demonstrates the impact these diseases have had on smallholder farmers in Africa. Ethiopia has the largest population of small ruminant livestock in Africa with nearly 49 million of these animals in the nation. A study of a livestock market in Ethiopia found that of the 1432 sheep and 1128 goats tested, over 18% of all sheep and 22% of goats, had been infected and were carrying their respective poxviruses (Yune and Abdela, 2017, p 1-2). These numbers showcase just how prevalent these diseases are among livestock in certain regions in Africa. Another case study showcases just how devastating these diseases can be, as one farmer’s outbreak led to a 49% mortality rate among their livestock and took the farm over 6 years to reach pre-outbreak levels of livestock populations (Yune and Abdela, 2017, p 4). Overall livestock diseases including SPV and GPV result in nearly 25% of all livestock in Africa perishing each year. Studies have also shown infection by either SPV or GPV have been found to reduce milk yield by 30%, and decrease contraception by 32% (IDRC, 2016, p 22). It is estimated that yearly Sheep and Goat Pox disease results in over 479 million USD in losses for smallholder farmers in Africa (IDRC, 2016, p 23).

About the vaccines, are they effective? And what are the costs?

Several different companies produce their own vaccines for both sheep and goat pox, including institutions in Africa, like the National Veterinary Institute in Ethiopia and Animal Health and Veterinary Biologicals, which produce their own vaccines for their nations (Hurisa and Jing, 2018, p 1; Barman and Catterjee, 2010, p 76). As little as one dose of these approved vaccines have been shown in some studies to provide strong lifelong protection against these poxviruses. (Hurisa and Jing, 2018, p 2.). However, some studies have found the opposite, and in certain countries, with evolving strains, a yearly vaccine is needed to keep up strong enough levels of immunity (IDRC, 2016, p 30). One study found that these vaccines provided 90% protection from all illness in the first 12 months and within that time had 100% protection from severe illness (Ammanova, 2021, p 15). Although certain studies have contradicted themselves on the duration of the immunity created by these vaccines, no studies have shown these vaccines being ineffective in protecting these herds from severe outcomes even when immunity wains after the initial year (IDRC, 2016, p 30). Despite these vaccines not being 100% effective, studies have shown that vaccinating an entire farmer’s livestock does provide enough herd immunity to limit and control outbreaks of these diseases (Hurisa and Jing, 2018, p 2). It has been found that the minimum vaccination rate to have strong enough herd immunity to prevent severe outbreaks is 75% (IDRC, 2016, p 24). In one study in Nigeria the economic benefits of vaccination outweighed the costs (in pounds by sterling) “by £372.87 and £42.46 in sedentary herds and £1752.79 and £180.10 in transhumance herds at 50 % subsidy levels” (Rawlins, 2021, p 16). Therefore, if governments provided farmers with as little as a 50% subsidy to provide access to these vaccines, the economic benefits far outweigh the costs of these vaccines.

Issues in the African Vaccination Effort

There are several issues in the current rollout and application of Sheep and Goat Pox vaccines throughout Africa. In many nations in Africa, including Ethiopia, the rollout and application of these precious vaccines are controlled by governments. In a case study in Ethiopia, this caused several problems in the nation’s vaccine effort. Several times these officials have been found to neglect farms that were a longer distance away, and instead only vaccinated local farms near their clinic (Aregahagn and Tadesse, 2021, p 5). There also have been several instances in Ethiopia where vaccinated livestock populations on farms have been found to have been given ineffective vaccines, which has been attributed to poor training in administrating the vaccine and faulty cold storage systems in the nation (Aregahagn and Tadesse, 2021, p 5). Another issue facing these vaccination efforts is the fact that in several nations in Africa, local smallholder farmers are ignored by their governments and not provided with programs to pay or provide them with these vaccines (IDRC, 2016, p 39). This is shown by the differing levels of vaccination across Africa. In 1997, Morocco achieved a sheep pox vaccination rate of 80%, while Tunisia and Algeria reached rates below 50% (Chehida, 2017). This causes several issues as eradication cannot be achieved without a continent-wide effort in Africa.

Solutions Today and Conclusion

Despite the vast number of issues facing these vaccination efforts, there are several workable solutions to help mitigate these issues. First, the desire for these sheep and goat pox vaccines is very high (surveys found it to be at least 97%), which means the first barrier of farmer’s consent is nearly negligible (IDRC, 2020, p 1). The Canadian International Food Security Research Fund based in Ottawa, Canada, did a research project on the issue around Sheep and Goat Pox vaccines and created several solutions to the main problems they found. They created a single-dose vaccine, that was heat stable, and did not require refrigeration, which would be ideal for smallholder farmers in Africa (IDRC, 2020 p 1). They found a local South African company to produce this vaccine in the continent as well, which will make it more localized and cheaper for many African nations (IDRC, 2020, p 1). This project also acknowledged the issue of training and educating local officials and farmers who would be responsible for vaccinating these animals. They created a program and directly trained 288 farmers and healthcare officials to use the vaccine properly, with thousands more trained indirectly through literature and remote learning (IDRC, 2020, p 2). This program and many others like it are investing money in creating solutions for improving vaccine rates in Africa. However, as will be seen in the charts below, this problem is not improving over time. As seen in the information throughout this paper, there needs to be more effort to reach smallholder farmers and eliminate government corruption and ineffectiveness which has plagued these efforts.

Additional Information to Get Started

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nQwfcufDtS4 This video shows the process of how smallholder farmers receive vaccinations for their small ruminate animals in India. It follows one worker’s average day providing both vaccinations and education to farmers.

https://www.idrc.ca/es/node/28084 This is a report on the IDRC’s single dose vaccine project and its expected outcomes for smallholder farmers in Africa and across the globe

https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/2727/41470.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y This is a full report by the IDRC on sheep production throughout Asia. It examines numerous countries and the issues they are facing, including lots of information on sheep pox in those nations.

https://agriculturepost.com/icar-ivri-transfers-technology-csf-sheep-pox-vaccine-to-hester-biosciences/ This is an article about a new sheep pox vaccine made at ICAR-Indian Veterinary Research Institute. They believe this new vaccine will increase protection over a longer period and be affordable enough for lower income farmers.

https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/81537 This is a good guide for smallholder farmers in Africa that must deal with Sheep and Goat Pox. This provides a detailed guide on the symptoms, ways to mitigate spread, prevent outbreaks, and why vaccinations are beneficial and needed.

https://www.libyanvet.com/Books/10%20Poxviridae.pdf This is a scientific virology review of all poxviruses including Sheep and Goat Pox. This is a good read for those scientifically inclined and wanting to know more about these two viruses’ genetics.

https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/2.07.13_S_POX_G_POX.pdf This is the World Organization for Animal Health manual for diagnostic tests and vaccines for all livestock. Within this manual is information on both tests and vaccines for Sheep and Goat Pox

Figure 1. This picture shows the first reported occurrences of Sheep and Goat Pox throughout the globe (Chehida, 2017).

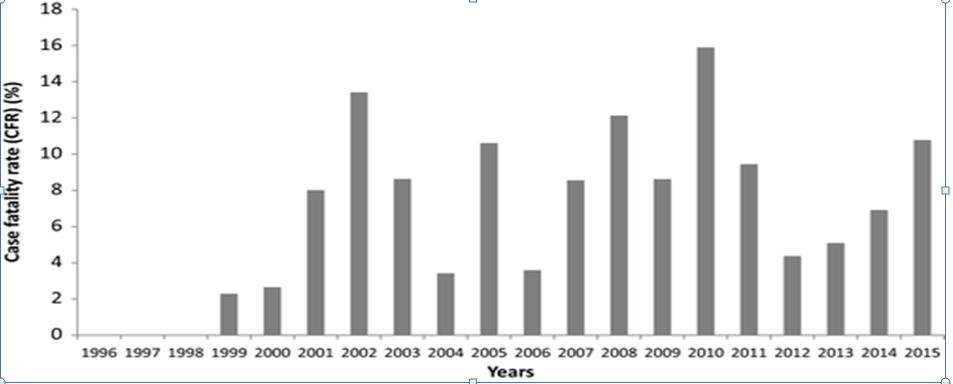

Figure 2. This chart shows the fatality rate of sheep and goat pox over a 16-year period from 1999-2015. (Chehida, 2017)

References

1. Aregahagn, S. and Belege, T. (2021) Spatiotemporal Distributions of Sheep and Goat Pox Disease Outbreaks in the Period 2013-2019 in Eastern Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Veterinary Medicine International, 2021. 1-7.

2. Amanova, Z. Zhuguissov, K. Barakbayev, K. (2021) Duration of Protective Immunity in Sheep Vaccinated with a Combined Vaccine against Peste des Petisis Ruminants and Sheep Pox. Vaccines. 9. 1-18.

3. Barman, D. And A. Catterjee, C. Guha, U. Biswas, J. Sakar, T.K Roy, B Roy, S. Baidya (2010). Estimation of post vaccination antibody titre against goat pox and determination of protective antibody titre. Small Ruminant Research, 93. 76-78.

4. Chehida, B.F. and E. Ayari-Fakhfakh (2017). Sheep Pox in Tunisia: Current Status and Perspectives. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 65, 50-63.

5. Hurisa, T.T. And Zhizhong, J. Guohua, C. Xiao-Bing, H. (2018). A Review on Sheep pox and Goat pox: Insight of Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment and Control Measures in Ethiopia. Journal of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology, 4. 1-8.

6. International Development Research Centre (2020). Improving Food Security in Africa with Novel Livestock Vaccines. International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Ottawa. 1-3. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/handle/10625/58597

7. International Development Research Centre (2016). Sheep and Goat Pox: Disease Monograph Series 22. International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa. 1-44. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/handle/10625/58272

8. Rao, T.V.S. and S.K Bandyopadhyay (2000). A comprehensive review of goat and sheep pox and their diagnosis. Animal Health Research Reviews, 1, 127-136.

9. Rawlins, M.E. Limon, G. Abedeji, A.J. Ijoma, S.I. (2021) Finial Impact of Sheeppox and Goatpox and Estimated Profitability of Vaccination for Substinance Farmers in Selected Northern States of Nigeria. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 198. 1-17.

10. Yune, N. And Nejash, A. (2017). Epidemiology and Economic Importance of Sheep and Goat Pox: A Review on Past and Current Aspects. Journal of Veterinary Science and Technology, 8. 1-5.