Chapter 9.5

9.5 - Amaranth leaves as a source of protein and nutrients

Kirsten Figliuzzi, University of Guelph, Canada

Suggested citation for this chapter.

Figliuzzi,K (2022)Amaranth leaves as a source of protein and nutrients,The Encyclopedia for Small Scale Farmers. Editor, M.N. Raizada, University of Guelph, Canada. http://www.farmpedia.org

Background

Amaranth is a genus of plant that has the potential to solve nutrient deficiencies in developing nations (National Research Council, 2006). It is eaten both as a leafy green vegetable and for its grain, and is grown in around 50 countries (National Research Council, 2006). Amaranth is considered an under-utilized crop, and is largely unknown by the western world (Alemayehu, 2015). This is a shame considering that amaranth helps feed and nourish many people living in developing nations today (National Research Council, 2006).

One of the most distinguishing qualities of amaranth vegetable is its high protein composition (Alemayehu, 2015). The protein score of amaranth (as defined by WHO) is 74, which is higher than most commercial crops (wheat: 47, rice: 69, soya bean: 68-89 and maize: 35). Amaranth also contains a very balanced amino acid composition which is close to the levels recommended by FAO/WHO for a healthy human diet (Alemayehu, 2015). It is high in the essential amino acids histidine and lysine, as well as the non-essential amino acid arginine (Alemayehu, 2015).

Amaranth vegetable contains high levels of vitamins and minerals (Onyango et al 2012). The two vitamins that appear in the highest quantities in amaranth are vitamin A and vitamin C. Amaranth also contains high levels of important minerals such as iron, calcium and phosphorus (Onyango et al 2012). Lastly, amaranth has significant levels of antioxidants due to the presence of flavonoids (Amaranth: Future-Food, 2009). All in all, the nutritional value of amaranth is considered higher than wheat, maize, soya bean and milk (Alemayehu, 2015).

In addition to nutrient quality, amaranth is also highly regarded because of its ability to grow under a number of adverse growing conditions (Alemayehu, 2015). Amaranth is a crop that matures very quickly, leaves can be harvested as early as 3 weeks after planting. This is a key characteristic for amaranth to have, because it can alleviate hunger by acting as a supplemental food source in the time between harvests of longer-growing crops (National Research Council, 2006). This period, when food is the most scarce, is often referred to as the “lean season” and it contributes considerably to hardship and hunger (USAID, 2015).

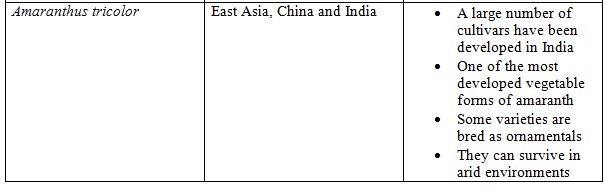

There are about 60 species of amaranth worldwide (USDA, 2016). All are annuals which produce small seeds. Most of these species consist of weeds which are not cultivated. The subset of this species which is cultivated can be divided into three groups: ornamental amaranths which are grown for their beauty, vegetable amaranths which are grown for their foliage and grain amaranths which are grown for their seeds (USDA, 2016). There are currently 18 species of amaranth which can be used to produce food available at the World Vegetable Centre (AVGRIS, 2016). For a description of five of the most common species used for food see Table 1 in Appendix 1.

Other Benefits

Amaranth plants have many additional uses. For example, it can be sold in the local market, making it a cash crop (FAO, 2006). Amaranth is also used as a traditional medicine for conditions like tape worms, high blood pressure, and urinary and throat infections (Alemayehu, 2015). It can be used as a highly nutritious animal feed (Amaranth: Future-Food, 2009), as a type of firewood, or as a dye for the colours red, green and yellow. Amaranth can also be used as a cover crop and can be intercropped with taller plants like banana, cassava and trees because it is shade-tolerant (National Research Council, 2006).

Besides the many uses of vegetable amaranth, amaranth grain can be used as a nutritious food source (National Research Council, 2006). Amaranth plants will produce a very large amount of seed which can either be used for planting, or can be used as a grain. This grain is often parched and milled into flour in a process similar to most cereals (National Research Council, 2006). Grain amaranth has significantly higher amounts of certain minerals including calcium, iron, phosphorus, potassium and zinc (USDA, 2016). However, its protein content is lower and is only about 11-12% (Amaranth: Future-Food, 2009).

Growing Amaranth

Amaranth does well in hot, humid environment (National Research Council, 2006). They can tolerate a range of temperatures between 22-40˚C. Amaranth can be grown in upland areas, as most species can survive in altitudes up to 800 m (National Research Council, 2006). The nitrogen requirements of amaranth are about 40 kg/ha (Onyango et al 2012). The use of either livestock manure, or legumes in preceding crop rotations should provide enough nitrogen to the soil (Alemayehu, 2015). If these nitrogen-boosting practices are not available, nitrogen fertilizer will substantially boost yields (National Research Council, 2006). The pH of the soil should be around 5.5-7.5 however some cultivars will tolerate a higher and more alkaline pH. Amaranth thrives in a variety of soil textures but will do best in sandy, well-drained soil with a high organic content (National Research Council, 2006). Amaranth can survive on as little as 200 mm of rain in a year, making it very drought tolerant (Grosz-Heilman et al 1990). Despite this drought tolerance, irrigation immediately after planting is advantageous (OMAFRA, 2012).

Amaranth is normally grown from direct seeding (National Research Council, 2006). The seeds are broadcasted and then covered with a tiny layer of soil (National Research Council, 2006). The soil covering should be about 1-2 cm thick and the seeds should be planted at a rate of 2.2 kg/ha (Myers, 2000). The seedlings are normally grown in nursery beds and then are transplanted one they are big enough (National Research Council, 2006). Within a month (in warm weather and high rainfall within 3 weeks) the plants are large enough to either be eaten or transplanted. Once amaranth is mature, they are a very easy vegetable to grow and require very little attention (National Research Council, 2006).

Amaranth has very large yields and can be harvested several times in one growing season (National Research Council, 2006). The entire plant can be harvested and eaten, but it is more common for just the young shoots and leaves to be picked. On a 10 m squared plot as much as 30-60 kg of vegetable has been produced. One way to keep amaranth plants producing leaves instead of going to flower is by repeated pruning and pinching of the plants as well as keeping the plants thoroughly watered (National Research Council, 2006).

Seed yields are much more variable and are highly dependent on cultivar and environmental conditions (Alemayehu, 2015). For dry land, seed yields between 450-700 kg/ha are reasonable while on land that gets high levels of rainfall or is irrigated, a seed yield of between 900-2000 kg/ha is reasonable (Alemayehu, 2015).

Cooking Amaranth

Amaranth leaves have a soft texture with a very mild flavour, similar to artichoke, and no trace of bitterness (National Research Council, 2006). The leaves are first boiled and then are often put into soups and stews or pushed through a sieve and served as a puree. The leaves and stems should only be boiled for a few minutes in order to reduce nutrient losses. The leaves should turn an emerald green colour after boiling. It is important to note that the colour of the water that the amaranth is boiled in should turn a dark colour. This darkened water should be tossed away and should not be consumed because it contains compounds which interfere with our ability to utilize nutrients. Young leaves will contain less of these compounds which is why it is important to harvest amaranth early and regularly (National Research Council, 2006).

Amaranth grain also has a variety of uses (Mburu et al. 2012). These include being popped, or toasted. Amaranth flour can be used to make tortillas, cookies and bread among other things (Mburu et al. 2012).

Potential Problems

There may be issues with the acceptability of amaranth, which may hinder its incorporation into the diets of people who are not accustomed to it (Elbien, 2013). Katherine Lorenz has been introducing amaranth into the diets of the people living in rural Oaxaca, a state in Mexico (Elbien, 2013). Lorenz found that there was a very low adoption rate when amaranth was being introduced as a staple crop for local consumption. Even though its nutritional benefits were being promoted, many farmers still opted to stick to their local diets. Lorenz found that the best way to promote this crop was to promote it as a cash crop. Once the locals realized they could sell it for money, there were higher instances of amaranth being grown, and farmers were therefore more likely to eat it (Elbien, 2013).

Don Lotter, who was involved in projects to introduce amaranth into San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala also speculates that a big problem in amaranth adoption rates is advertisement (Lotter, 2005). He suggests that without massive advertising campaigns, amaranth has a poor chance of becoming a staple food for local peoples (Lotter, 2005).

These kinds of integration projects also take time (Puente, 2016). For example, Puente, an organization that promotes amaranth consumption in areas of Mexico, took 11 years (from 2003-2014) to get 15% of targeted families to adopt amaranth into their diets. In this organization, adoption into diets is categorized by amaranth being eaten 2-3 times a week. However, with ongoing persistence, this adoption rate number is projected to be closer to 50% by 2017 (Puente, 2016).

Although amaranth does not have any major diseases associated with it, it does still have several minor growth inhibiting issues (Alemayehu, 2015). The major fungal diseases associated with amaranth are damping-off fungal disease of seedlings, and cankers. In order to reduce the instances of damping-off, seedbeds must be well drained and ideally located in sunny areas (National Research Council, 2006). Various fungicides have also been proven effective against these diseases (National Research Council, 2006). Currently, there are not any fungicides labelled for use on amaranth, therefore, diseases have to be managed through proper site selection (Center for Crop Diversification, 2011).

Amaranth also has several pests associated with it (National Research Council, 2006). Leaf-chewing insects often pose a serious threat (National Research Council, 2006). Despite being susceptible to insects, amaranth is considered very resistant to nematodes (Alemayehu, 2015). Amaranth can be an effective means of controlling nematode populations when it is placed in crop rotations with plants that are more susceptible to nematodes (Alemayehu, 2015).

Practical Resources

An amaranth production guide from the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries department for the Republic of South Africa can be found at: http://www.nda.agric.za/docs/Brochures/Amaranthus.pdf

An amaranth production guide from the World Vegetable Center can be found at: http://203.64.245.61/web_crops/indigenous/Grow_Amaranthus.pdf

A guide on saving amaranth seed from the World Vegetable Center can be found at: http://203.64.245.61/web_crops/indigenous/amaranth_seed.pdf

The following website are some suppliers of amaranth seed

A supplier of amaranth seed located in India is Raj Foods International which can be found at: http://www.rajfoods.co.in/products/amaranth-seeds.html

A supplier for Amaranthus hybridus seed for areas in South Africa is the company Organic Seeds which can be found at: http://www.organicseed.co.za/62-amaranth

A supplier of several different amaranth species is the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System which can be found at: https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/search.aspx

West Coast Seeds supplies the species Amaranthus tricolor as well as several other species and can be found at here: https://www.westcoastseeds.com/shop/vegetable-seeds/amaranth-seeds/red-leaf-amaranth-seeds/

Picture Based Lesson to Train Farmers

For the South Asian version (pictures only, text for you to insert), click this link for lesson 10.5:http://www.sakbooks.com/uploads/8/1/5/7/81574912/10.5_south_asian.pdf

For the East/South Asian version (pictures only, text for you to insert), click this link for lesson 10.5:http://www.sakbooks.com/uploads/8/1/5/7/81574912/10.5e.s.a.pdf

For the Sub-Saharan Africa/Caribbean version (pictures only, text for you to insert), click this link for lesson 10.5:http://www.sakbooks.com/uploads/8/1/5/7/81574912/10.5subsaharan_africa_carribean.pdf

For the Latin-America version (pictures only, text for you to insert), click this link for lesson 10.5:http://www.sakbooks.com/uploads/8/1/5/7/81574912/10.5latin_america.pdf

Source: MN Raizada and L Smith (2016) A Picture Book of Best Practices for Subsistence Farmers. eBook, University of Guelph Sustainable Agriculture Kit (SAK) Project, June 2016, Guelph, Canada.

Further Reading

Information about the Amaranth: Future-Food Project can be found at: http://www.amaranth-future-food.net/Amaranth.asp

More information about grain amaranth published by the Jefferson institute can be found at: http://amaranthinstitute.org/sites/default/files/docs/Amaranth_crop_guide.pdf

Information about the value of amaranth seed oil on the international market can be found at: http://www.marketsandmarkets.com/PressReleases/amaranth-seed-oil.asp

The nutritional value of boiled amaranth leaves from the United States Department of Agriculture can be found at: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/2817?manu=&fgcd=&ds=

Information about Puente, an organization that promotes amaranth growth in areas of Mexico can be found at: http://www.puentemexico.org/content/mission-and-values

For more information about the varieties of seed available at the World Vegetable Centre see: http://203.64.245.49/AVGRIS/search/characterization/amaranthus

For more information on growing amaranth and on different species of amaranth see the following paper: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/121422/2/AAE%20No.90003.pdf

For more information about amaranth see the following book chapter in the book Lost Crops of Africa: Volume 2: Vegetables, available at https://www.nap.edu/read/11763/chapter/3

Table 1: Characteristics of some of the most common types of amaranth used for food regularly (National Research Council, 2006).

References

1. Alemayehu, F. R., Bendevis, M. A., & Jacobsen, S. ‐. (2015). The potential for utilizing the seed crop amaranth (amaranthus spp.) in East Africa as an alternative crop to support food security and climate change mitigation. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science, 201(5), 321-329.

2. Amaranth: Future-Food. (2009). Adding Value to Holy Grain: Providing the Key Tools for the Exploitation of Amaranth- the Protein-Rich Grain of the Aztecs. Retrieved from http://cordis.europa.eu/docs/publications/1235/123543221-6_en.pdf

3. AVGRIS. (2016). Vegetable Genetic Resources Information System.Amaranthus. Retrieved from http://203.64.245.49/AVGRIS/search/characterization/amaranthus

4. Center for Crop Diversification. (2011). University of Kentucky- College of Agriculture. Grain Amaranth. Retrieved from https://www.uky.edu/Ag/CDBREC/introsheets/amaranth.pdf

5. Elbien. S. (2013). The Seeds That Time Forgot. Retrieved from https://www.texasobserver.org/the-seeds-that-time-forgot/

6. FAO. (2016). Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations. Amaranth. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/traditional-crops/amaranth/en/?k

7. Grosz-Heilman, R., Gold, J. T., & Helgeson, D. L. (1990). Amaranth: a food crop from the past for the future. (missing information)

8. Lotter, D. (2005). Amaranth: The ideal crop to add to a small farmers’s polyculture in developing nations? Retrieved from http://www.newfarm.org/international/pan-am_don/may05/

9. Myers-RL. (2000). Amaranth: new crop opportunity. Progress in new crops: Proceedings of the Third National Symposium Indianapolis, Indiana, 22 25 October, 1996, 207-220.

10. National Research Council. (2006). Lost Crops of Africa: Volume II: Vegetables. Crops (Vol. II, pp. 33-51). National Academies Press.

11. OMAFRA. (2012). Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Grain Amaranth. Retrieved from http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/CropOp/en/field_grain/spec_grains/gama.html

12. Onyango, C. M., Harbinson, J., Imungi, J. K., Shibairo, S. S., & Kooten, O. van. (2012). Influence of Organic and Mineral Fertilization on Germination, Leaf Nitrogen, Nitrate Accumulation and Yield of Vegetable Amaranth. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 35(3), 342-365.

13. Puente. (2016). The Numbers. Retrieved from http://www.puentemexico.org/content/the-numbers

14. USAID. (2015). United States Agency for International Development. For second year, USAID continues extraordinary effort to avert famine in South Sudan. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do/agriculture-and-food-security/food-assistance/jun-16-2015-usaid-effort-avert-famine-south-sudan

15. USDA. (2016). United States Department of Agriculture. Amaranthus spp. Retrieved from https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/50301000/Reference_Documents/Amaranth.pdf

16. USDA. (2016). United States Agency for International Development. USDA food composition databases. Retrieved from Foods List